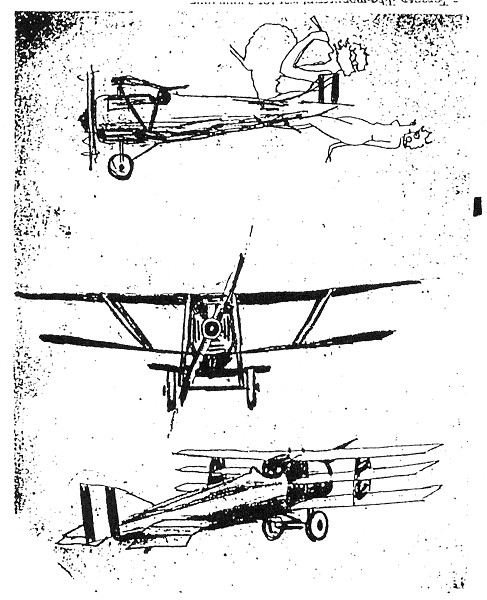

| 1. Because of its originality and unique style, the fictional work of William Faulkner has been viewed as difficult. Challenged by this difficulty, academic study of his literary style started in the 1960s, and has borne considerable fruit. 1 There are as many difficult points in Faulkner’s fiction as there are achievements. One of these problematic areas, as recent feminists and cultural materialists, such as Richard Godden, point out, is its “penurious habit of secretion” (Zender 4-6). By this phrase is meant that at the first reading - or sometimes even several readings – the reader is disturbed by the opacity of the discourse and the confusing events. To find a reason for this phenomenon, we can mention some of Faulkner’s basic traits. He was very concerned about privacy. Then, in common with many other modernist writers, he held the view that objectivity is a synthesis of subjectivities. Furthermore, Faulkner’s moral scruples can be noticed. Let us take an example of the latter trait in one of his latest novels, The Mansion, especially the part where Linda Snopes Kohl says to Gavin Stevens, “But you can me.” At this point the narrator adds “The explicit word, speaking the hard brutal guttural in [her] quacking duck’s voice.” Nobody speaks a word to fill the space. But judging from the context, such as the remarks by the narrator and Stevens, there should be some word in the blank which means Linda’s desire of sexual intercourse. Faulkner left the blank in the text and made the meaning clear though context alone, showing moral restraint. Regarding this opacity, a comparison with Ernest Hemingway is suggestive. Hemingway’s hard-boiled, direct style is a kind of “sketch,” which conveys the bare facts. 2 As for the meaning, readers can grasp the gender roles in his fiction by reference to the gender code of his era. We can say that Hemingway wrote plain fiction in the sense that it contributes to the study of gender in his time. In comparison, Faulkner’s fiction is more complex. The point at issue in the scene in The Mansion is not Linda’s existence as a deaf-mute nor as a transsexual. It is rather that Faulkner concealed a taboo word which Linda uttered and tried to rephrase the word through the voices of men, like the narrator and Stevens, but in an understated way. This narrative device indicates Faulkner’s sensibility to the gender code and the constraints of gender performance, in other words, his moral scruples. This attitude accounts for the gap between the gender code and gender performance of the characters in the fiction on the one hand and their representation on the other. Faulkner’s moral restraint makes the discourse and the events in the fiction ambiguous. The end result is vagueness. So finally, Faulkner’s manipulation of opacity and vagueness accounts for the difficulty found by many readers in his fiction. Faulkner “secretes” or hides his fictional characters’ ideas, expressing them indirectly through the interplay of characters in a series of hints. In addition, his characteristic usage of words and fictional techniques intensifies this “secretion,” making the works less accessible to the reader. One element of Faulkner’s style which contributes to its indirectness is the usage of personal pronouns. Carl Zender points out that the pronouns in Faulkner’s fiction serve to secrete and opacify the discourse and events in his works (44-52). For example, some “we” and “they” pronouns in "Rose for Emily" and Light in August are used to represent the group whose inner character cannot be guessed from outside, and which is thus an area of secrecy. Multiple viewpoints, which is characteristic of the modernist Faulkner, also contribute to the secretion and the opacity. Four characters in The Sound and the Fury and fifteen characters in As I Lay Dying narrate from the first-person point of view. These “I”s vividly represent their inner world; however, they simultaneously present ambiguity in that individuals are free to show or hide their feelings. The study of Faulkner’s style largely focuses on his prose, with its modernistic, intricate technique of writing. However, his “habit of secretion,” using ambiguous personal pronouns can be also found in his poetry, although it is generally viewed as Romantic. 3 Let us examine one of his earliest poems, “Portrait.” Faulkner started his literary career as a poet, and wrote “Portrait” in 1921. “Portrait” is regarded as a poem about a woman, who is called “you.” The woman, however, keeps hanging her head and hiding her eyes and her face finally disappears, in spite of the fact that a portrait is generally defined as a depiction of someone, especially recognizable by his or her face. But with the unspecific personal pronoun “you,” “Portrait” keeps secreting the identity of the subject to the end, and thus makes the reader wonder whose “Portrait” it is.4 When did Faulkner’s “penurious habit of secretion” begin? It might be said to have been his “habit” since the earliest days of his career. The “habit” can be seen in one of Faulkner’s earliest poems, “The Lilacs.”5 “The Lilacs” is the first poem in The Lilacs, his first substantial collection of poetry, although it was not commercially published. It is a poem where three airmen under the lilacs reminisce about their sortie in a fighter plane and how they were shot down. One of the characteristics of the poetry is the heavy use of personal pronouns. In addition, the personal pronouns are used very ambiguously, both in the tangle of singular and plural and also in the difficulty of identifying their antecedents. As a result the poem is confusing. In the first strophe, a man soliloquizes “Lest we let each other guess/ How pleased we are/ Together here…,” but he does it as if they do not let the reader “guess/ How pleased we are/ Together here.” “The Lilacs” seems to have been a very important poem for Faulkner. We can state this because he repeatedly put the poem in other collections of poetry, especially at the beginning of each collection. Nonetheless, the poem has received scant critical attention, apart from appreciations by Margaret Yonce and Judith L. Sensibar. Especially Yonce pointed out that though “The Lilacs” is seemingly narrated by three soldiers, it is actually a dramatic monologue, soliloquized by one soldier, suggesting the division of his self. Yonce’s work is illuminating in that it raises the question of the narrative of the poem. However, she did this without identifying the antecedents of the pronouns, which are used in a very ambiguous and complex manner. Rather, we would suggest that an analysis of the particular use of the pronouns would also lead to the conclusion of the division of an airman’s self. Furthermore, with some effort we can identify clear antecedents of many pronouns, and thus clarify the poem. This would enrich our understanding of “The Lilacs,” and illustrate Faulkner’s “penurious habit of secretion” even in his earliest work. Moreover, this study of an early poem would yield some clues to the origin of the structure of Faulkner’s subsequent novels. What did Faulkner try to secrete, or hide, through personal pronoun manipulation, which plays such a major role in the opacity of the poetry? Conversely, what did he try to surreptitiously reveal? In this paper, first, we show that Faulkner’s characteristic personal pronoun usage was present even in his earliest literary works. Second, by identifying the antecedents of the pronouns, we clarify the poetry’s narrative structure. Finally we disclose some hidden aspects of the poetry. 2. We start with reviewing the factual origin the “The Lilacs.” As mentioned earlier, “The Lilacs” is a poem where three injured airmen reminisce about being shot down in the First World War. They became airborne, to stalk “a white woman,” “a white wanton” or “nymph.” Then, they “felt her arms and her cool breath/ A red rose on white snows, the kiss/ of Death,” which led to their planes being shot down. “The Lilacs” can be viewed as both war poetry and love poetry, and in fact it has been described as both. No doubt this duality is based on Faulkner’s experience. Faulkner’s beloved Estelle married another man, an event which caused Faulkner to enlist as a volunteer. After the war, Faulkner limped in his hometown as if he had been injured in the conflict. However, according to his biographic data published later, it seems that Faulkner was demobilized without having been on a single sortie. It leads us to the guess that his failure to win a scar in the war added to his troubles. The background above suggests that it reasonable to view “The Lilacs” as both war poetry and love poetry. 6 Now let us review the text of “The Lilacs.” In the first strophe, “I,” one of the three airmen narrates the events: the three sit under the lilacs. In the second strophe he says that some young women nearby speak to them, saying “Shoot down,” “Poor chap―Yes his mind.” Then in the third strophe he makes clear their situation: “We sit in silent amity.” 7 From the fourth strophe on, the airmen start to reminisce about the war, which is the part in question. In the fourth strophe, the soliloquist speaking to one of the other two soldiers says “I, old chap, was out before the day.” He explains that “I” tried to catch “a white woman,” or “a white wanton,” with the “machine.” However, in the fifth strophe the reader realizes that it was “we,” more than one person, who set took off in the fighter plane, by the soliloquist’s words “We mounted up and up,” “found her” and “felt her arms and her cool breath.” On the other hand, in the next line the soliloquist says “The bullet struck me here” and “The bullet killed my little pointed-eared/ machine. I watched it fall”: the reader understands that just one person “I” flew in the fighter. This suspicion is confirmed in the next strophe, the sixth. The soliloquist regrets the accident, saying “The bullet struck me here.” He continues in this vein with “One should not die like this” and “One should fall I think to some/ Etruscan dart,” and utters in the last line “Instead, I had a bullet through my heart.” In short, the soliloquist “I” suggests that only of the three men took part in a mid-air battle. It is something of a puzzle to unravel who is “we” and who is “I,” and why the singular and plural first person pronouns are mixed. “The Lilacs” confuses the reader by this ambiguous usage. Certainly three airmen are depicted in the poem, but how many of them were in the warplane? If they did not fly, how did they come to be injured? Returning to our textual analysis, we come to the seventh strophe. In the first line the soliloquist declares, “―Yes, you are right,” commiserating with and justifying the soliloquist who said “One should not die like this” in the sixth strophe. These two different voices indicate that the soliloquist in the seventh strophe is a different airman from the one who speaks in the previous strophes. The new soliloquist says “We were too young.” It suggests that he flew in the same plane as the previous soliloquist and was shot down with him, contradicting the words “The bullet struck me here” in the fifth strophe. In the eighth strophe, just after the soliloquist starts the first word “Still,” an utterance is inserted: “―he draws his hand across/ his eyes.” This seems to refer to a different person who is coolly observing his comrade who has just started his story with the word “Still.” Who is this man? What is the purpose of this interpolated phrase suggesting an observer? Furthermore, though the soliloquist who says “Still” in the first line begins relating another downing of a warplane with the lines “We had been/ Raiding over Mannheim,” are all of the three airmen involved in this raid or only two of them? The soliloquist in this strophe talks to the other soldier(s), “You’ve seen/ The place?” This could concern one, two, or all the three of the airmen. But if only one or two men went there, why were the others also injured? Were the others injured because of downing of the warplane during the stalk of “a white woman,” which took place before the raid over Mannheim? Indeed there remains the possibility that all three of them were on the plane then. As seen above, the ambiguous usage of personal pronouns and the consequent ambiguity of the text are characteristic of Faulkner’s style even in his earliest works. However, we cannot critically approach “The Lilacs” by merely making the fundamental comment that it can be read as both war poetry and love poetry, but we need to explain the meaning of its personal pronouns. There are more questions in addition to what has been discussed so far, but because of space limitations, we should now start identifying the antecedents of the ambiguous and complicated personal pronouns with a view to solving the questions of the narrative. 3. It is certain that a single soliloquist, who says “The bullet struck me here,” soliloquizes in the first three strophes of the reminiscence (the fourth, the fifth and the sixth strophes). But in the seventh strophe another soliloquist enters, judging from the fact that he states compassionately “―Yes, you are right” to the soliloquist who says in the previous strophe “One should not die like this,” and the former soliloquist justifies the latter. Indeed, the soliloquists of the sixth and seventh strophes have contrasting characters. While the contents and the expression of the former’s soliloquy are romantic, those of the latter’s, such as the reference to the family, are realistic. Now to avoid confusion, let us call the romantic soliloquist from the fourth through the sixth strophe S1 and the non-romantic, realistic soliloquist who suddenly appears in the seventh strophe S2. In the seventh strophe, S2 continues showing his sympathy for S1. Identification of the antecedents of the soliloquist’s “we” and “I” in the eighth strophe is difficult because the topic of Mannheim suddenly starts; there seems to be an abrupt change of topic between the seventh and the eighth strophes. But the next, ninth strophe provides some clues. We notice the following four parts: firstly, the dots at the end of the eighth strophe, secondly, the beginning of the ninth strophe “His voice has dropped and the wind/ is mouthing his words/ While the lilacs nod their heads……/ Agreeing while he talks,” thirdly, the following lines “And care not if he is heard, or is/ not heard,” and, finally, the last line but three “One should not die like this.” These parts suggest that S1 or S2 soliloquizes in the eighth strophe and continues soliloquizing from then onward. Simultaneously, we also notice the ending lines of the ninth strophe: “One should not die like this―/ Half audible, half silent words/ That hover like grey birds/ About our heads.” This passage shows that the soliloquy in the eighth strophe developed from the reminiscence from the third through the seventh strophe, and that a man nearby is calmly listening to the monologue continuing for a while but gradually disappearing as if in a dream, with a distance from the soliloquy and the conversation in all the parts of the reminiscence. Indeed, we notice earlier a detached observer, who says “―he draws his hand across/ his eyes” just after the soliloquist’s first word “Still.” Who is this detached observer? He is not S1 or S2, because these two are absorbed in their conversation. Thus the other third airmen do not join the conversation when it turns to reminiscence. Let us call the airman S3. We can say that S1 or S2 is the soliloquist in the eighth strophe and that S1 or S2 went to Mannheim, and that S3, who is just listening to their story about Mannheim, did not join them. Now, is the soliloquist in the eighth strophe S1 or S2? Did both S1 and S2 go to Mannheim or not? Why does S3 only listen without commenting throughout the reminiscence section?―it seems that he does not need to show himself in the poem. And why are the personal pronouns confusing? In other words, who boarded the warplane? To answer these questions we find some clues at the beginning of the tenth strophe. There is a line “We sit in silent amity” at the beginning of the tenth strophe immediately preceding the reminiscence section. This line serves as a marker, dividing the poem into two parts, the reminiscence and the present. However, the sentence “We sit in silent amity,” raises a question. The three airmen sit in silence, apparently contradicting the conversation of S1 and S2 in the reminiscence section. The two characters utter words in silence: an impossible dialogue. Is “The Lilacs” a poem about telepathy? Or is it a kind of a parody which makes no sense to the reader? How can the dialogue in silence be achieved? Only one answer remains. That is, “The Lilacs” is one person’s internal soliloquy. In other words, S1 and S2 are in S3’s mind. If S1 is S3’s voice of sadness and romantic imagination, as can be seen in his imagination of “Etruscan,” and S2 is S3’s non-romantic, realistic voice of sympathy for romantic S1, that is, of S3’s self-justification, we can understand the strange narrative in “The Lilacs.” As Yonce also pointed out, it is not strange at all even if “we” boarded the warplane or “I” did it, because all of the characters are S3’s voice. 8 It is suggestive to refer to the draft of “The Lilacs,” which Faulkner wrote in 1918. Here the line “We sit in silent amity” just before the reminiscence section, moving away from the present, was followed by a line “[John the poet, James the [motor del.] motor del.] salesman, and myself/ John the poet, talks to James and me” (Brodsky 37). It follows that “myself” or “me” in the draft is S3, the soliloquist in the present from the first to the third strophe; that “John the poet” is the romantic S1, the soliloquist from the fourth strophe at the beginning of the reminiscence section to the six strophe; that “James the motor salesman” is the non-romantic, realistic S2, the soliloquist who sympathized with S1 in the seventh strophe; and that in the present from the tenth to the last strophe, “myself” or “me”―S3―is again the soliloquist. In short, we detect a tripartite structure: first “myself” or “me” soliloquizes in the present in the first three strophes. Then the voices of a romantic “poet” and a non-romantic, realistic “motor salesman” are internal voices in “myself” or “me” in the reminiscence from the fourth to the ninth strophe. Finally, “myself” or “me” soliloquizes again in the present from the tenth to the last strophe. This, therefore, is the essential narrative structure of “The Lilacs.” With this structure in mind we can therefore say that “The Lilacs” is a poem where the romantic voice and the non-romantic, realistic voice in “me” talk to “myself.” The two voices address the “me” who did not board the fighter, about a sortie in a fighter, frequently using ambiguous personal pronouns, starting with “I, old chap, was out before the/ day.” To be more accurate, it is a poem where “me,” who did not board the fighter, is listening to his own imagined voices about a sortie in a fighter and his injuries when his plane was shot down. We confirmed earlier that “we” boarded the fighter but the bullet struck “me” (S1), but it makes sense if we understand that the romantic voice in “me” (S3) was shot down, while the other non-romantic, realistic voice (S2) in “me” (S3) offers sympathy. This view might be open to the objection, “How can we explain how all the three airmen, including S3, were injured?” The explanation of this is that it was not their bodies but their minds that were injured. In the second strophe, where S3 is the soliloquist, the women nearby says, “Shot down… Poor chap―Yes his mind.” In effect, the airmen have mental rather that bodily scars. We will close this chapter with a discussion of the raid over Mannheim. After stalking “a white woman,” or “a white wanton,” the airmen were more dead than alive. None of them are fit to fly again soon, and thus could take part in a raid over Mannheim. In addition, in the latter half of the eighth strophe, the mention of the plane shot down during the raid over Mannheim is followed by the line “One should not die like this” again. This is a repetition of the line following the reminiscence of the plane shot down stalking “a white woman,” or “a white wanton.” So we see that the shot-down plane at Mannheim is a re-use of the image of the plane shot down stalking the woman.9 4. The foregoing analysis permits us several conclusions. First, when Faulkner wrote the airmen’s soliloquies, it was all fictional. He hinted at an early stage that he did not go on a sortie in a fighter plane nor win a scar in an aerial battle. Thus we know that he was just pretending, well before the biographical study by Joseph Blotner. The fact was, however, made ambiguous by Faulkner’s heavy and complicated usage of the personal pronouns in the poem. Second, as a consequence of the first, “secretion” or opacity of the discourse, partly achieved by his usage of the personal pronouns, is a fundamental characteristic of his style from his earliest poetry to his later prose. Third, we cannot agree with Sensibar’s contention that Faulkner’s conversion from a poet to a novelist occurred as he gradually distanced himself from the mask which he used in his poetry. This is evident from our reading of “The Lilacs.” There the soliloquist plays a role of a listener to his own imaginative voices. In addition, we confirmed earlier that the soliloquist is hearing that the romantic voice (S1, or “John the poet”) in “me” (S3) has been shot down. This means that Faulkner kept a distance from his own romantic imagination rather than being absorbed in it, at least in his early literary career. Also, as long as the soliloquist is just a listener to his own imaginative voices, Faulkner left space between himself and his own non-romantic, realistic voice, too. We cannot say that Faulkner’s poetry is characterized either by his romantic imagination or his non-romantic, realistic voice. On the other hand, we can assert that his poetry shows the ineffectuality and powerlessness of both the voices. Discussions of “The Lilacs” often include a mention of the lilac theme in TheWaste Land by T. S. Eliot. If this is relevant, the lilac flowers of “The Lilacs” should be a symbol of regeneration. However as mentioned earlier, the lilacs here are dissimilar to Eliot’s. Here they are indifferent to the soliloquist; “The Lilacs” over his head “care not if he is heard, or is/ not heard.” In other words, Faulkner’s lilacs make no promise of regeneration. It is the “make no promise” that Faulkner wrote in his poetry. Put another way, Faulkner’s poetry shows that whether it is romantic on one hand or non-romantic and realistic on the other, the voice―or, word―has no power of regeneration; it is merely useful for remembering spent passion, or as Eliot put it in the first strophe of The Waste Land “Memory and desire stirring.” 10 Later, Faulkner started writing prose fiction works. One of their features is that their protagonists are contrasted in a particular way, in a romantic/realistic duality. One of them is like a romantic poet. The other is like a child of capitalism, such as a salesman, who loves an automobile. Faulkner wrote his prose with these contrasting characters, and additionally sometimes used a technique of multiple viewpoints. Do these techniques make Faulkner a modernist novelist? By no means. They can be found in his earliest works such as the poem “The Lilacs.” It could not be said that Faulkner ended his poetic phase and then started his career as a novelist; rather his prose and poetry are one. Thus his novels share many characteristics even of his early poems, such as “The Lilacs,” the first poem in his first collection of poetry. Though Faulkner returned home without having experienced combat in a fighter plane in the First World War, he lived as a cripple in his hometown as if he had been scarred in battle. On the other hand, he described a heartbroken airman, hinting in his poetry that he had never flown in combat and that his physical disability was just a pretence, through the ambiguity achieved by manipulation of the personal pronouns. James G. Watson pointed out that the contents of Faulkner’s work stem from his consciousness of being in the public eye. Indeed his ambiguous and complicated technique of writing and the difficulty of his fiction resulted from his sensitivity to others’ gaze and voices. (This is a revised version of the paper read at the 88th General Meeting of The Japan Society of Stylistics, November 19, 2005.) (An earlier form of this paper first appeared in the Journal of Osaka Sangyo University: Humanities. vol. 120, 2006, 1-16.) Notes 1 In the 1970s, Faulkner’s style of writing was investigated in various ways, such as words and terms, syntactic structure, metaphor, narrative structure, time and tense, point of view, linkage between technique of narrative and theme like the South. In the 1980s, the focus moved to the lack in information in Faulkner’s fiction, based on deconstruction by Jack Derrida, narratologie by Gerard Genette, theory of motive for rhetoric by Kenneth Burke, and theory of dialogue by Mikhail Bakhtin. In the 1990s, investigation of the relation between the subjectivity and the representation through the analysis of the narrative of fiction and between the concept of community and the technique of the narrative, became popular. 2 Regarding this discussion about Hemingway, see Miura’s “Subject without Aura.” 3 In the situation that the study of Faulkner’s style of writing is mainly on his prose, Judith Lockyer suggests the importance of his style of writing poetry, pointing out that Faulkner’s aspiration for poetic soliloquy can be found in the narrative of his prose. 4 Conversely, however, there is a possibility that the identity of the portrait is the author himself who wrote “The Portrait,” expecting the look or the voices of “you,” unspecified young women who are his contemporaries. See Suzuki’s “Performance of a ‘Portrait’.” 5 Regarding each strophe in “The Lilacs,” see the text quoted later. 6 This can be also found expression in the drawing of a plane lying on that of a couple, which was drawn by Faulkner. See the drawing at the end of this paper. 7 All the italics in the quotations are by the author. 8 Regarding the reminiscence, Sensibar insists “other characters comment on the “we” as if we were here only one person” (67). In short, Sensibar thinks, in contradiction to Yonce, that several soldiers are soliloquizing. But Sensibar’s opinion cannot explain how the soldiers talk to each other “in silent amity.” 9 With the meaning of Eros and Tanatos given to the word Mannheim (= Mann + Heim), the failure to attack Mannheim might suggest the soldier’s broken heart because of lost love and dishonor in the war. 10 Later Faulkner wrote about powerlessness of word in his prose like Mosquitoes. Bibliography: Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. New York: Random House, 1974. Brodsky, Louis Daniel and Robert W. Hamblin (eds). Faulkner: A Comprehensive Guide to the Brodsky Collection. Volume V: Manuscripts and Documents. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1988. Faulkner, William. “The Lilacs.” Louis Daniel Brodsky and Robert W. Hamblin (eds) Faulkner: A Comprehensive Guide to the Brodsky Collection. Volume V: Manuscripts and Documents. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1988. 46-50. Godden, Richard. Fictions of Labor: William Faulkner and the South’s Long Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Lockyer, Judith. Ordered by Words: Language and Narration in the Novels of William Faulkner. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1991. Miura Reiichi. “Subject without Aura: Gender Image and Formation of Literature.” Image and Culture: Language and Culture Research Series vol. 1. Faculty of Language and Culture, Graduate School of Languages and Cultures, Nagoya University (2002): 123-138. Sensibar, Judith L. The Origins of Faulkner’s Art. Austin: U of Texas P, 1984. Suzuki Akiyoshi. “Performance of a ‘Portrait’: On ‘Portrait’ by William Faulkner.” Journal of Osaka Sangyo University: Humanities. vol. 116 (2005): 167-180. Yonce, Margaret. “‘Shot Down Last Spring’: The Wounded Aviations of Faulkner’s Wasteland.” Mississippi Quarterly 31 (Summer 1978): 359-368. Zender, Karl F. Faulkner and the Politics of Reading. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2002. “The Lilacs” [A printable PDF version is available here.] Ⅰ We sit drinking tea Beneath the lilacs on a summer afternoon Comfortably, at our ease With fresh linen napkins on our knees We are in Blighty And we sit, we three, In diffident contentedness Lest we let each other guess How pleased we are Together here, watching the young moon Lying shyly on her back, and the first star. Ⅱ There are women here, Smooth shouldered creatures in sheer Scarves, that pass And eye me strangely as they pass. One of them, my hostess, pauses near. ―Are you quite all right, sir?―she stops to ask. Will you have more tea? Cigarettes? No?― I thank her, waiting for them to go, To me they are as figures on a masque. ―Who?―Shot down― Yes, shot down―Last spring― Poor chap―Yes, his mind― Hoping rest will bring― Their voices come to me like tangled rooks Ⅲ Busy with their tea and cigarettes and books. We sit in silent amity Ⅳ ―It was a morning in late May A white woman, A white wanton at the edge of a brake A rising whiteness mirrored in a lake And I, old chap, was out before the day Stalking her through the shimmering reaches of the sky In my little pointed-eared machine. I knew that we could catch her when we liked Ⅴ For no nymphs ran as swiftly as they could. We mounted up and up, And found her at the border of a wood A cloud forest, And pausing at its brink We felt her arms and her cool breath A red rose on white snows, the kiss of Death. The bullet struck me here, I think, In my left breast And killed my little pointed-eared machine. I watched it fall The last wine in a cup…. I thought that we could find her when we liked. But now I wonder if I found her, after all. Ⅵ One should not die like this On such a day From hot angry bullets, or other mod- ern way. From angry bullets One should fall I think to some Etruscan dart On such a day as this And become a tall wreathed column; I should like to be An ilex tree on some white lifting isle. Instead, I had a bullet through my heart― Ⅶ ―Yes, you are right One should not die like this, And for no cause nor reason in the world. Tis right enough for one like you to talk Of going into the far thin sky to stalk The mouth of Death, you did not know the bliss Of home and children and the se- rene Of living, and of work and joy that was our heritage, And best of all, of age. We were too young. Ⅷ Still―he draws his hand across his eyes ―Still, it could not be otherwise. We had been Raiding over Mannheim. You’ve seen The place? Then you know How one hangs just beneath the stars and seems to see The incandescent entrails of the Hun. The great earth drew us down, that night. The black earth drew us Out of the bullet tortured air A black bowl of fireflies… Ⅸ There is an end to this, somewhere; One should not die like this― One should not die like this― His voice has dropped and the wind is mouthing his words While the lilacs nod their heads on slender stalks, Agreeing while he talks And care not if he is heard, or is not heard. One should not die like this― Half audible, half silent words That hover like grey birds About our heads Ⅹ We sit in silent amity I shiver, for the sun is gone And the air is cooler where we three Are sitting. The light has followed the sun, And I no longer see The pale lilacs stirring against the lilac-pale sky. XI They bend their heads toward me as one head ―Old man―they say― When did you die?… XⅡ I―I am not dead. I hear their voices as from a great distance―Not dead He’s not dead, poor chap; he didn’t die― We sit, drinking tea. (Underlines and Roman numbers are by the author. The lines indicate citation in the text.)  (Brodsky 17) Copyright (c) 2008 Akiyoshi Suzuki |